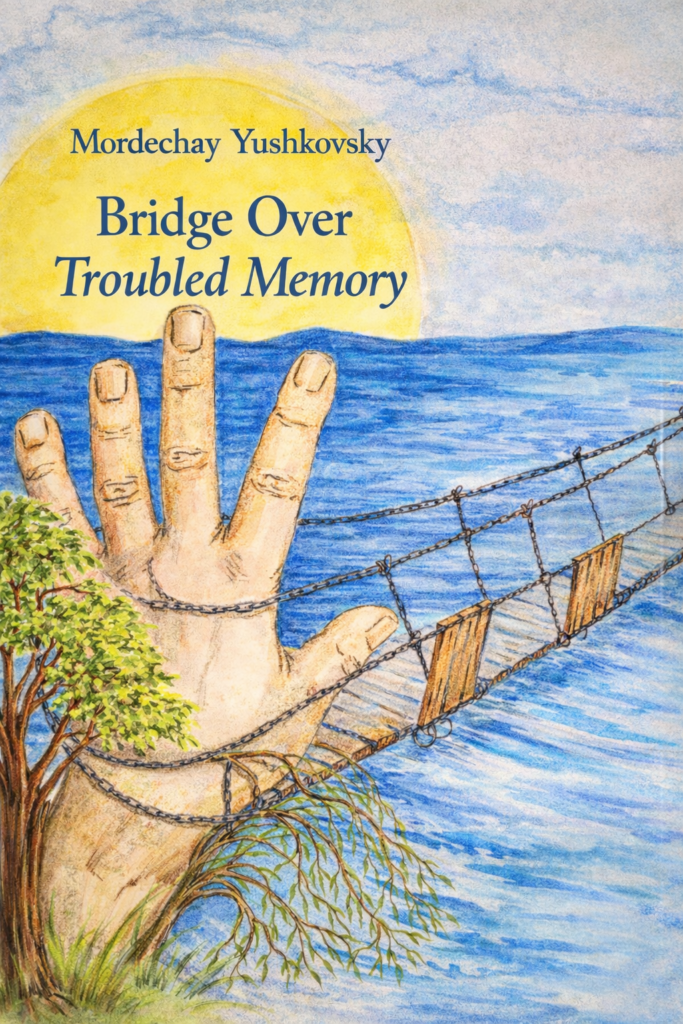

“Bridge Over Troubled Memory” is a collection of autobiographical stories exploring Jewish life in the Soviet Union and Israel through the lens of Yiddish language and culture. Yushkovsky weaves personal narratives of Holocaust survivors, Soviet antisemitism, and cultural preservation, creating a bridge between past and present while honoring those who carried Yiddish through history’s darkest moments.

“Bridge Over Troubled Memory” is a collection of autobiographical stories exploring the author’s deep connection to Yiddish language and culture while chronicling the Jewish experience in the Soviet Union and Israel. Through personal narratives and historical reflections, Yushkovsky creates a literary monument to a vanishing world. The book opens with a powerful introduction explaining the author’s devotion to writing in Yiddish. Born in Ukraine and raised during the late Soviet period amid institutional antisemitism, Yushkovsky discovered Yiddish through life itself – through encounters with remarkable people, family stories, and Vinnitsa, a city that still breathed remnants of Jewish culture. For him, Yiddish is more than a language; it is a way of life, a mode of thinking, an intimate emotional landscape. It represents the collective memory of the Jewish people, the language in which most Holocaust victims lived and perished, making it an eternal memorial to millions of martyrs. In “Where My Yiddish Comes From,” Yushkovsky traces his unlikely path to becoming a Yiddish writer in 1980s Soviet Union, contributing to the only Yiddish journal published during that era. Through stories of his grandparents, he paints vivid portraits of survival, loss, and resilience across generations scarred by war and genocide. “One Grandmother and Two Grandfathers” delivers a haunting account of the Holocaust’s devastation through his grandmother Brayne’s testimony. She recounts her husband Motel’s death at Stalingrad after volunteering for the front, and the horrific murder of her brother’s family during the Nazi occupation of Berditchev. The story of her niece Nusya – hidden by a Polish neighbor but betrayed and brutally murdered by a Ukrainian collaborator who once claimed to love her – stands as one of the book’s most searing moments. These memories raise profound questions about human cruelty, survival, and the weight of remembrance. “From Kharkov to Haifa” follows Dr. Arye Zeldin’s odyssey from Soviet antisemitism to Israeli freedom. His story encompasses persecution during the “Doctor’s Plot,” multiple attempts to enter medical school blocked by discrimination, and ultimately the difficult decision to emigrate to Israel. This chapter illuminates the systematic oppression faced by Soviet Jews while celebrating their determination to preserve dignity. “The Melody of Talmud as a Life-Saver” tells the remarkable story of Feivel Rayewitz, a Bundist who survived the Gulag thanks to an unexpected connection with a Jewish camp commander. When Feivel answered a question in Yiddish using the traditional Talmud study melody, the hardened officer’s humanity awakened, saving his life through preferential work assignments. This story demonstrates how cultural memory can transcend ideology and become a literal lifeline. Other chapters explore Yiddish cultural life in Israel, a love story set against historical trauma in Kiev, and the experiences of Soviet Jews navigating antisemitism while maintaining Jewish identity. Throughout, Yushkovsky interweaves his work as an educator and cultural activist, leading tours to Eastern Europe and teaching thousands about Yiddish culture. The book’s title metaphor recurs throughout: memory as a turbulent river that must be crossed, with language and culture serving as the bridge connecting past to present, loss to survival, destruction to renewal. Yushkovsky’s writing honors those who carried Yiddish through the darkest times while ensuring their stories endure for future generations. It is simultaneously a personal testament, a historical document, and a passionate argument for preserving endangered cultural memory.